February is Black History Month. Our nation has a long history of racist housing practices which prevented many Black Americans and other minorities from becoming homeowners and effectively restricted them to living in certain neighborhoods. The impact of these practices is felt to this day, with many cities still largely segregated along the lines originally drawn by redlining. Vermont can sometimes feel exempt from this history, given our small number of non-white households and still-rural landscape. However, our land use and zoning policies have had the effect of keeping Black and other minority Vermonters out of many communities.

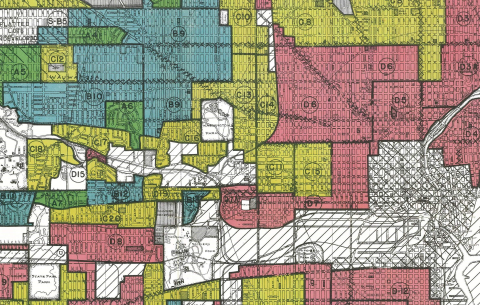

Redlining practices started during the mid-1930s through New Deal era housing programs. Federal agencies refused to insure home mortgages in ‘redlined’ or primarily Black neighborhoods while simultaneously subsidizing builders of whites-only suburban developments. Throughout this most of this period, Vermont saw limited development, with its population remaining mostly flat until after 1960.

Although Vermont was not formally redlined, there are still examples of racial segregation in the form of exclusionary housing covenants. These were written into property titles to prevent them from being sold to or occupied by members of a given race, ethnic origin or religion. Until they were outlawed in 1968 by the Fair Housing Act, they were often used by real estate developers to keep new subdivisions entirely white. At least two neighborhoods in South Burlington had housing covenants that forbade non-white residents. A slavery reparations initiative currently underway will include searching deeds to determine the prevalence of racially restrictive covenants among Burlington homes. It is possible that deeds to other Vermont homes across the state still retain the now-unenforceable provisions.

Despite our comparatively limited history of systemic racist housing practices, Vermont does still have a history of decisions around zoning and land use, which have had the effect of determining who lives in a community. Many Vermont communities, particularly more suburban communities, have largely retained mid-century zoning practices that discourage multifamily housing or more dense development. These types of zoning codes were often consciously designed to exclude renters and lower income homebuyers, with the full knowledge that Black and other minority households were more likely to fall into those groups.

Although we often think of our state as simply rural, economist Art Woolf has noted that Vermont’s wealthiest communities surround cities and employment centers that have much lower household incomes. This is very similar to patterns in other states, albeit on a much smaller scale. Vermont’s Black households are more likely to have low incomes and are far more likely to be renters than white households. Burlington alone is home to 30% of Vermont’s Black households, despite the city accounting for just 6% of Vermont’s households.

Whether intentionally planned or not, we have built many communities that almost exclusively serve white households. As Vermont slowly grows more diverse over time, we run the risk of perpetuating and deepening racial divides in our state if we do not change our zoning practices to allow for a wider range of home types and income levels.

Pictured: A mortgage lending map used by the Federal Home Owner's Loan Corporation (HOLC) showing redlined neighborhoods in Milwaukee